What was special about Pittville’s mineral water?

Chris Archibald

Mineral v spa water

Spa water is made available via a pump and a tap in a spa building in a spa town. The term ‘spa water’ is often used, but strictly speaking it should be referred to as “mineral water". Spa water is water rich in minerals from which it derives its properties, and the water can arguably be said to be beneficial to health. The word ‘spa’ comes from the name of the town of Spa, near Liège in eastern Belgium, a fashionable health resort for hundreds of years, and it is ultimately related to the Belgian Walloon word espa ‘fountain’. The waters at Spa, rich in minerals, have been drunk since the 14th century, and are still sold today under the simple title of ‘Spa’.

Courtesy of Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum

History of Cheltenham as a spa town

Cheltenham was a small rural town with a population of around 1,500 people when in 1716 William Mason, a hosier and a Quaker, noticed the saline water, which it was believed could cure all kinds of illness, in a field he had bought in Bayshill, on land which now forms part of the Ladies’ College. Henry Skillicorne, Mason’s son-in-law who inherited the land and the spring through his wife Elizabeth, decided in 1738 to develop a business selling subscriptions to take the waters. He built a well around the spring, installed a pump and raised a protective structure over the well together with assembly rooms and additional buildings necessary for those feeling the effects of the waters. During the years of 1739 and 1740 he planted avenues of trees to create the Old Well Walk, a spa, and the first pleasure garden in Cheltenham.

In 1740 Dr Short published his History of Mineral Waters praising Cheltenham’s waters, which aroused much interest and encouraged royalty, wealthy and influential visitors, and the gentility to visit. There were around twenty-six spas in Cheltenham. The Pump Room was the last and the grandest, but it was really built too late to benefit from the enthusiasm for Cheltenham as a spa town, which began to wane in the late 1830s. Each of the spas, mainly small, had its own focal point and offered water with a slightly different mineral composition. The generous reserves of underground water in the area meant that almost anyone could sink a well on their property and charge visitors for access to it.

Composition of and claimed cures for Cheltenham’s mineral waters

The original spa at Cheltenham was built on a slow spring oozing from the thick bluish clay under the sandy surface of the soil, which left salts on the surface. The geological formation underlying the land between the Severn and the Cotswold hills is mainly Lower Lias clay or limestone. The alkaline and saline waters of Cheltenham rise from the New Red Sandstone higher than the Vale, and the water, under pressure, is forced up through cracks and veins in the clay. The composition of the minerals in the waters is affected by the strata through which it passes. Cheltenham spa water contains unusually large amounts of salts. The minerals in the waters dispensed at the different spas were similar, but it was the amount of each mineral that gave the water its individual taste and effect. The Chalybeate Spa adjacent to Sandford Park had iron-rich waters, as did the Old Well Spa, but in a milder form. It was useful as a medical alternative to the mainly saline waters, as it was diuretic rather than laxative.

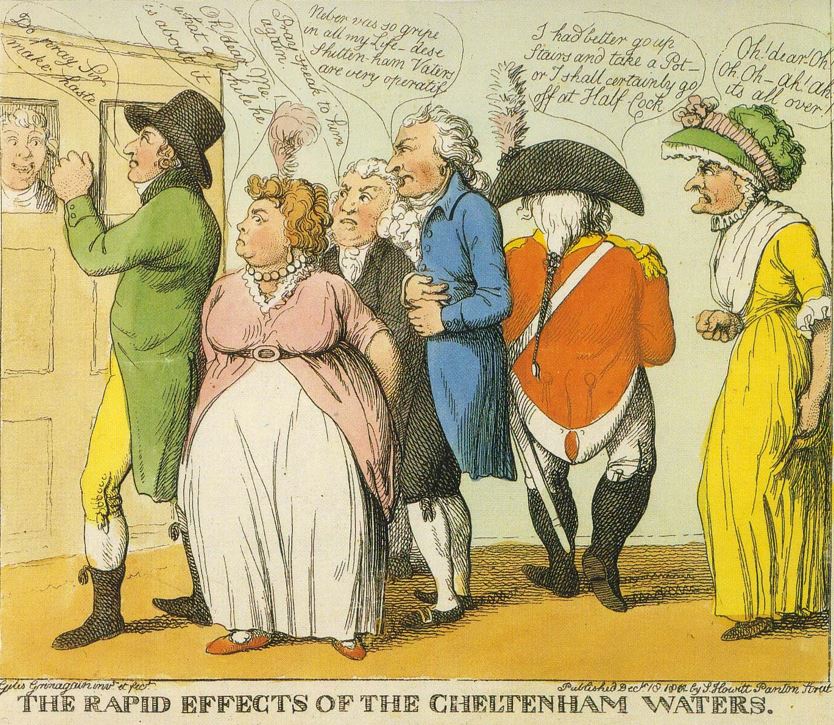

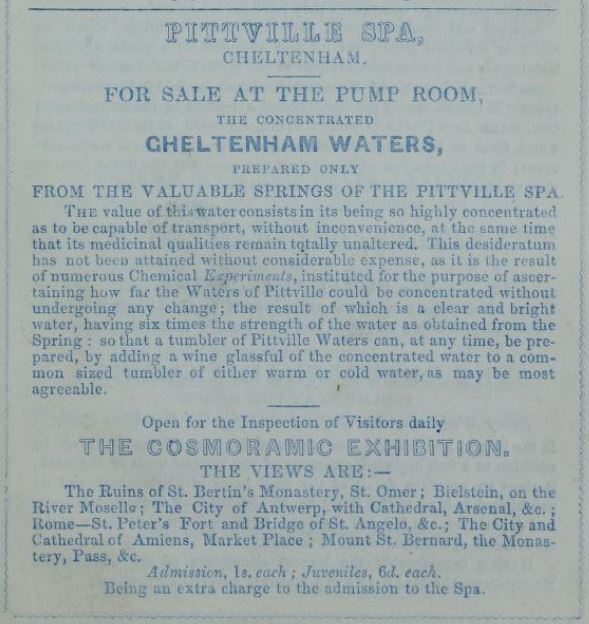

Rowe’s Illustrated Cheltenham Guide (1860), Advertisements p. xiii

All sorts of claims were made for the Cheltenham spa waters, suggesting they were a cure for a wide range of afflictions such as pimples, leg ulcers, nervous diseases, convulsions, chronic inflammation of the eyes, and female diseases. It would therefore appear that a trip to Cheltenham to take in the fresh air and waters after the excesses of London life would be a good idea to detox for the season. However, one had to take into account the limited knowledge of doctors at the end of the 18th and early 19th centuries and the lack of regulation, and there were plenty of ‘quacks’ hoping to profit from the unwary. Recommendation for how much water should be taken varied considerably according to the health of the patient. Cheltenham also provided much entertainment, which could undo any good work done by the waters.

Pittville Pump Room waters

Here is some information on the Cheltenham waters which were previously available in the Pittville Pump Room.

Firstly the taste: Steven Blake, in his booklet on the Pittville Pump Room, notes that “perhaps the best impression of the early days of Pittville and its spa is gained from James Buckman’s 1842 Guide to Pittville in which he wrote that ‘about the year 1822 a well was opened near where the Pump Room now stands, the waters of which were soon ascertained to possess a pleasant saline taste; in our younger days it was a pleasure eagerly sought after by ourself and companions to take a summer ramble through fields leading to the well..’ to taste the waters”. This is perhaps not the memory of everyone who has had the chance to taste the water. For the last three years the taste of minerals has been absent from the spa water, and in a blind-tasting test people could not tell the difference between the spa water and tap water.

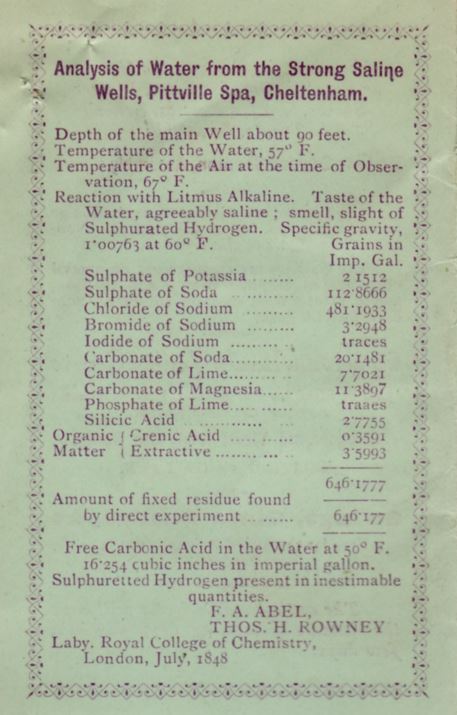

Secondly the mineral content (see the 1848 analysis below): Tests have shown that the waters under Cheltenham were mineral-rich, and although units in the 1848 analysis are in the form of ‘grains in an imperial gallon’ they do indicate the predominant minerals in the water.

The different ratio of the minerals in the water gives it its taste and properties. It has been observed that the content becomes weaker when the well is long drawn upon.

What benefit could be derived from the water?

The spa water contains the following minerals which research shows have medicinal properties, as follows:

Chloride of sodium - common salt – is an essential nutrient involved in numerous cellular and organ functions; however too much or too little can be harmful. Doctors use salt in saline drips, and it can be used as a flush to cleanse the colon and to treat constipation, as well as in eye washes.

Sulphate of soda or sodium sulphate is an inorganic compound soluble in water and better known as Glauber’s salt after the German-Dutch chemist and apothecary Johann Rudolf Glauber (1604-70). He discovered the chemical in 1625 in Austrian spring water and named it ‘sal mirabilis’ (miraculous salt) because of its medicinal properties. The crystals were used as a general-purpose laxative until more sophisticated alternatives came about in the 1900s.

Carbonate of soda or bicarbonate of soda (baking powder) can be used as an antacid to treat acid indigestion and heartburn.

Bromide of sodium has been used as a hypnotic, anticonvulsant, and sedative medicine.

Carbonate of magnesium is one of many magnesium salts used for the relief of symptoms such as dyspepsia, heartburn, and constipation.

Carbonate of lime can be used as an antacid, but too much can be dangerous.

Silicid acid is usually used in the form of an ointment for warts, acne, etc but can also be used to treat ringworm.

The analysis mentions an agreeably saline smell, but also a slight odour of sulphurated hydrogen, which is not so pleasant.

There is much debate on the value in taking the waters but from the above it suggests that depending on the ailment and how the waters were administered they may well have had some beneficial effect. The effect would also have depended on the individual, and we are learning today about the human microbiome and gut microbes individual to each person. However people have been taking the waters for a very long time, so it would suggest there must be some benefit.

Pittville Pump Room wells and pumps

Over the almost two hundred years that mineral water has been served at the Pump Room a number of wells have been dug. The initial well was reportedly outside the footprint of the Pump Room. There is a manhole in the bank north of the car park over a well, but it is not known if this is the original well. The original pumping machinery can still be seen in the basement of the Pump Room; this would have been worked by hand (see photo), but now the pumps are operated by electricity.

Fly wheel, photo courtesy Catherine Martin

A report by the Borough Surveyors’ Department in 1888, written at the time when the Council were purchasing the Pump Room and pleasure gardens, makes interesting reading. It was reported at the time there was a vault at the back portion of the building, in which there was a well some seventy-two feet deep. There was also a surface-water well some fifty-five feet deep, which was necessary to prevent surface water mixing with the mineral water. The report went on to mention several other wells, one named the ‘sulphur well’ and another the ‘saline well’. It seems that new wells had to be dug to maintain the flow of mineral water and to stop it being diluted. Following the report they must have then carried out works to remedy the situation and it is likely that they also had to do this on other occasions in the following years.

There is also mention in the report of a powerful ‘still’ or apparatus used for making a ‘strong solution of saline’. A copy of an advertisement “For sale at the Pittville Spa the concentrated Waters prepared from the valuable springs of the Pittville Spa” has been found. Bottle it and sell it: nothing changes!

In 2003 the water was cut off as it became contaminated with ground water. A new borehole was sunk and a well was built, the water coming up from ninety feet below; the work was funded by a local firm, Kohler Mira. It is on the south side of the Pump Room main hall and can be spotted by a discreet disc in the floor (for more information see the PRR leaflet - Pittville Pump Room, a brief history).

Where were all the loos?

Much has been written about the Pump Room and Pleasure Gardens, but there is no mention of the toilets similar to the provision at the Old Well. It can only be imagined that they were discreetly placed around the gardens and looked a bit like those in the cartoon.

Is Cheltenham no longer a spa town - where do we go from here?

The mineral water is not available for tasting in the Pump Room at present, and when last sampled it tasted like tap water. A reply to recent enquiries of the Council’s Property Department, responsible for provision of the waters, revealed that they were looking for a further specialist to advise on what is already a complex problem. Due to Public Health requirements they are currently double-filtering the water ,which may remove some of the minerals.

Hopefully this will be resolved by the Council in the near future, but it may need a sponsor similar to Kohler Mira to help restore the spa water to its former glory. The Pump Room was the last place in Cheltenham at which you could taste the mineral waters - so can Cheltenham still be referred to as a spa town?

I should like to thank Steven Blake for bringing to my attention the surveyor’s report mentioned above, and also the advertisement for the concentrated waters

Chris Archibald was a Chartered Civil and Structural Engineer and worked for much of his career on the design of infrastructure which included the Air Traffic Control Centre at Swanick, the St Georges Centre in Burton, and a village called Emmerdale.

Now retired, he is a Trustee of Friends of Pittville with responsibility for organising the Green Space Volunteers and helped Cheltenham Borough Council write the ten-year Management Plan for Pittville Park to obtain the Green Flag Award and Green Heritage Site Accreditation.

He is a member of Pump Room Revival with an interest in the waters at the Pump Room.

Based on a presentation given by Chris Archibald on 18 September 2021 in the grounds of Pittville Park, as part of Cheltenham's Heritage Open Days 2021.