Florence Earengey and Women’s Suffrage in Cheltenham

Sue Jones

Florence Earengey (1877 – 1963) was active in the women’s suffrage movement. She lived at 3 Wellington Square in Pittville between 1899 and 1911.

Early life

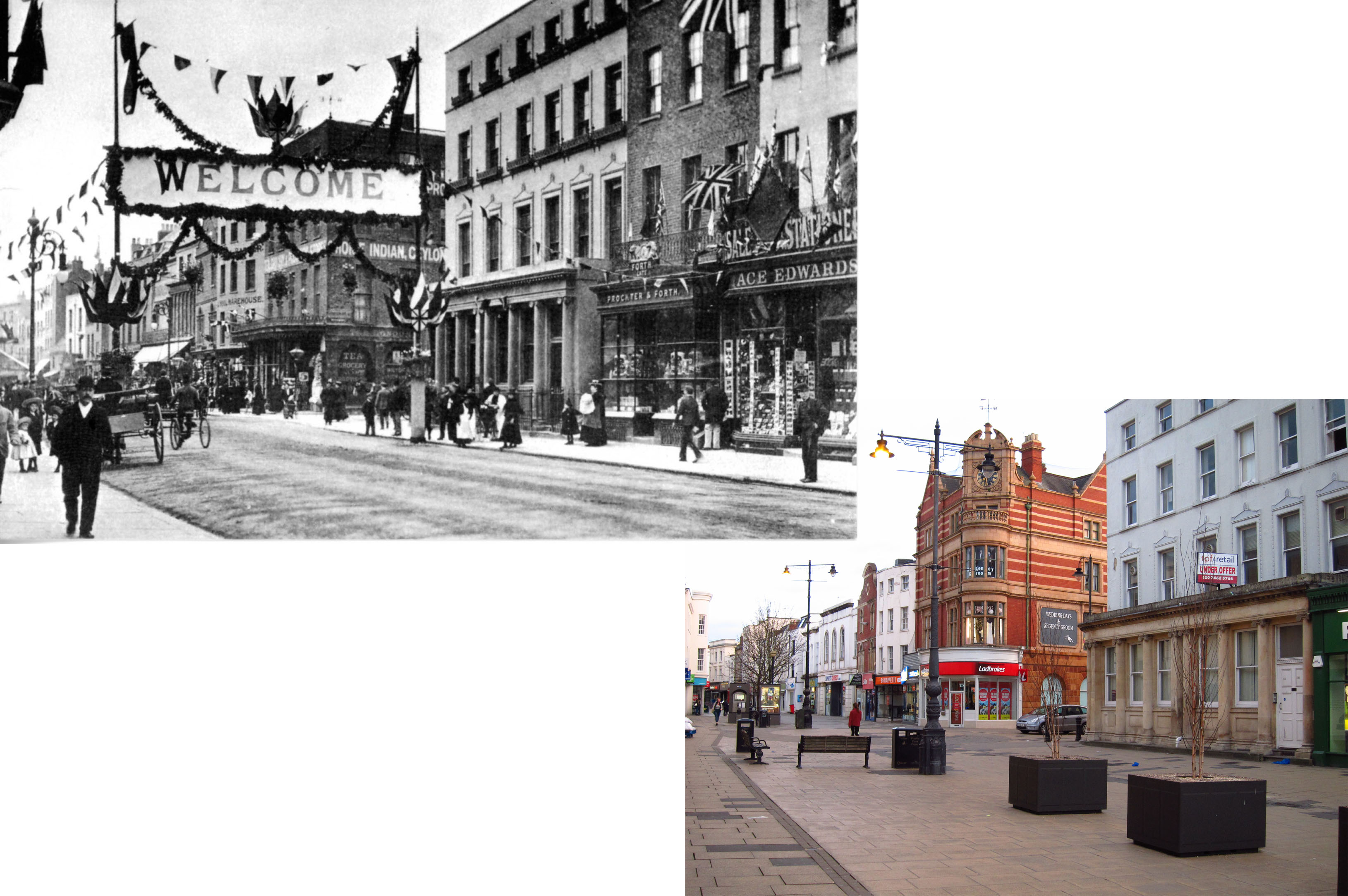

Florence Earengey (née How) was born in Cheltenham in 1877, the third of seven children and the second daughter of John and Hannah How. John How was a successful grocer and tea dealer whose London Supply Store, on the corner of the High Street and Cambray Place, had been built up from lowly beginnings.

John How’s London Supply store then and now

Photograph by P. S. Jones

John How began his working life as a live-in grocer’s assistant for another grocery business on the High Street. After he married Hannah Walker, formerly a domestic servant, in 1870, he set up his own business on Bath Road, advertising the sale of good tea at 2s per pound. He even applied for a drinks licence, in spite of being the son of a Baptist minister and marrying at Salem Baptist Church. By the time Florence was born, the family had probably moved to 33 Cambray Place and were running the new business from there.

Education

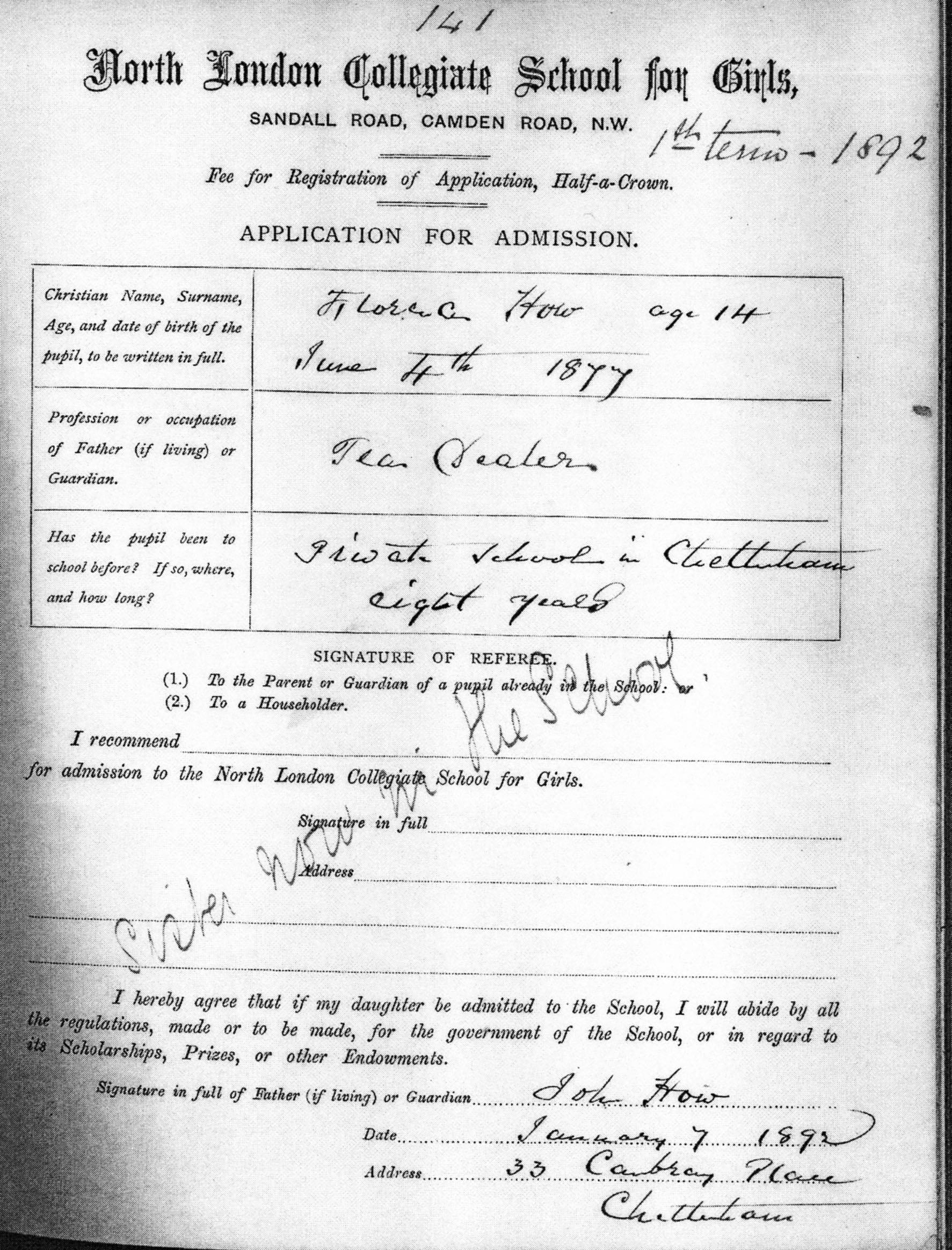

Florence attended The Hall School in Montpellier in Cheltenham and was then admitted to North London Collegiate School for Girls in 1892 at the age of 14. Her older sister Edith had already been a pupil there for two years.

North London Collegiate School Archives

North London Collegiate School would have provided the kind of academic education that Cheltenham Ladies’ College denied to girls whose fathers were ‘in trade’, and so it was a natural destination for Florence, her older sister Edith and younger sister Lilian. Florence subsequently gained a BA from London University in 1898; at least part of her degree was achieved through private study, after following a course at the University of Aberystwyth.

Marriage and move to Pittville

In 1899 Florence married William George Earengey, who had also gained a law qualification by private study from London University and was practising as a solicitor in Cheltenham. His father was a foreman and then clerk to a Cheltenham ‘click bootmaker’ (an expert at cutting leather). William had been educated at Highbury National School and Cheltenham Grammar School, so rose quickly from lowly origins, much like his father-in-law. The couple started married life at No 3 Wellington Square West, where they lived for the next stage of their lives and where they both became involved in the fight for women’s suffrage. Their daughter, Elaine Oenone, was born in 1904.1

3 Wellington Square West (the house with the white door)

Florence and the Suffrage campaign

Florence described herself as a rebel, attracted to radical causes, although she was less radical than her sister Edith How-Martyn, who joined the Independent Labour Party and then became national Joint Secretary of the Pankhursts’ Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1906. Florence also gave her early allegiance to the WSPU; there was a short-lived effort to set up a branch in Cheltenham in 1906, of which she became Honorary Secretary.

But the constitutional Women’s Suffrage Society (WSS) was more successful and, like many women in the town, Florence was at this stage prepared to support any group which espoused the cause. The Cheltenham Examiner records that she seconded the vote of thanks to Marie Stopes, the future birth control campaigner, at a WSS meeting,2 and at the end of 1906 she was elected to the WSS committee and continued to serve until 1910.3 Her husband William, an active local Liberal politician and Councillor for Central Ward from 1907, was also a supporter and often chaired public meetings and addressed WSS members’ meetings.

Dr. William Earengey with fellow Liberal campaigners for the municipal elections

Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 8 November 1913

Photo-edited by P.S. Jones

This adherence to a number of different groups was a common phenomenon in the period before positions became hardened as the WSPU’s tactics became more militant and controversial.

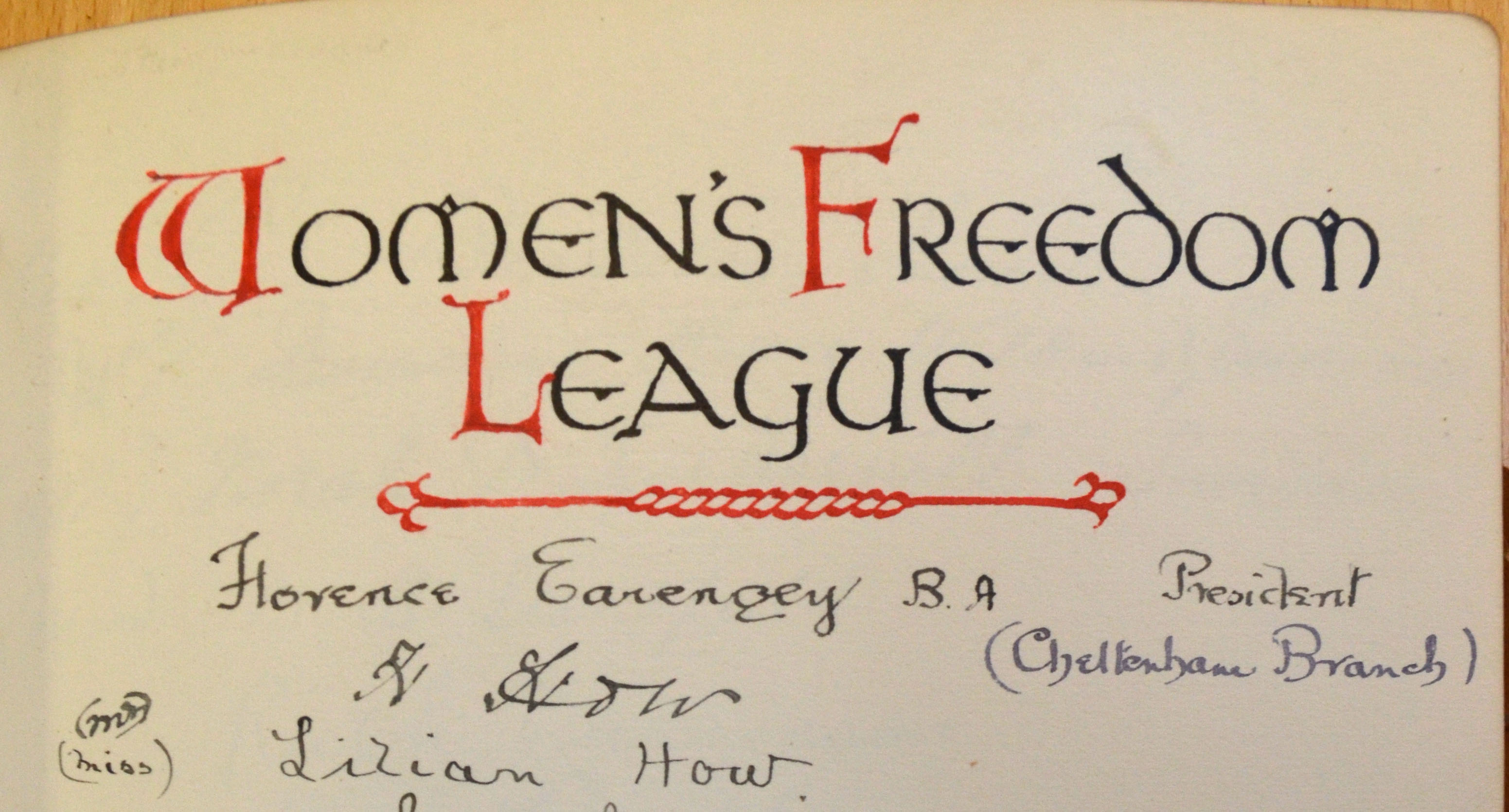

The breakaway Women’s Freedom League (WFL)

In 1907 there was a split at the top of the WSPU, in part because of discontent with the autocratic rule of the Pankhursts. Edith How-Martyn, together with Charlotte Despard and Teresa Billington-Greig, led a breakaway group and formed the Women’s Freedom League (WFL). This still fought for women’s suffrage with a radical agenda, and members were prepared to break the law if necessary, but not to use violence. Edith How-Martyn was its national Honorary Secretary from 1907 until 1911 and she came to Cheltenham early in 1908 to help her sister Florence form a local branch. Florence became the effective and very active leader of the WFL in Cheltenham until the outbreak of war, first as Honorary Secretary and then as President.

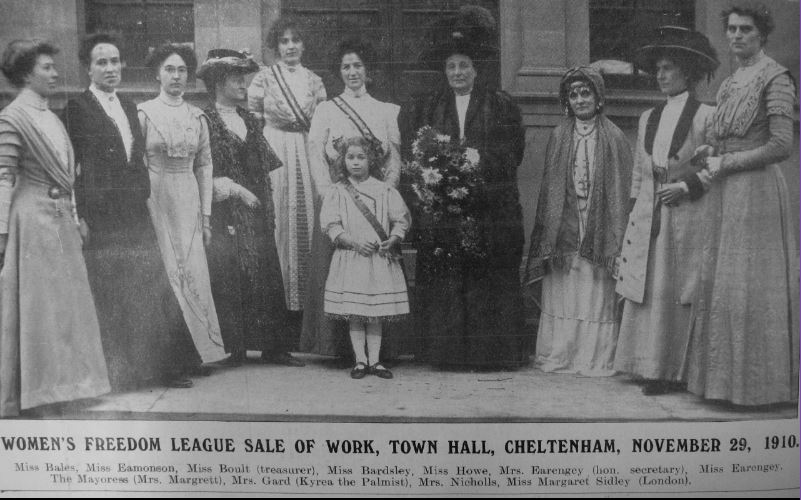

Florence (centre) with her daughter Elaine Oenone, then aged about 6

Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 3 December 1910

The WFL in Cheltenham held public meetings and often joined forces with WSS members. Florence was their spokesperson on many occasions and wrote to the local papers to clarify the WFL’s position on the violent methods used by the WSPU (the WFL was not prepared to damage persons or property).4

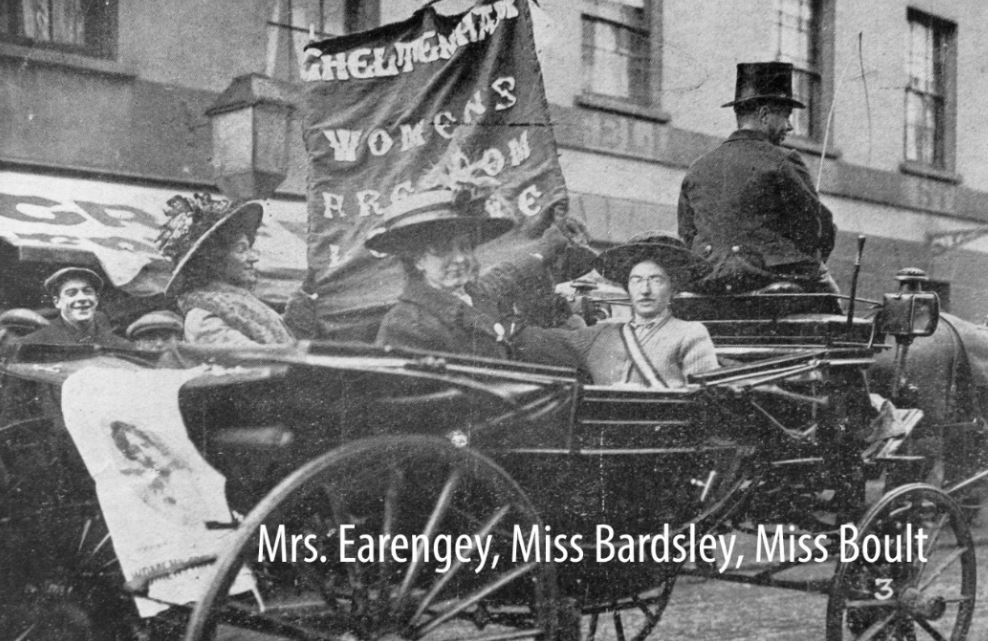

Cheltenham WFL leaders campaigning during the December 1910 election:

Mrs. Florence Earengey, Miss Bardsley, and Miss Boult.

Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 10 December 1910

In 1910, she and nine others in the WFL severed their formal links with the WSS. This was announced at the WSS Annual Meeting which her husband chaired! 5

The Earengeys also severed their links with Wellington Square, moving in 1911 to Ashley Road, Battledown, where they bought a plot for £300 and named their house Ashley Rise. This was a sizeable detached house, with 11 rooms; it moved them away from an environment where there had been neighbours sympathetic to the cause, such as Lucy March Phillipps who had lived next door to them in Wellington Square.

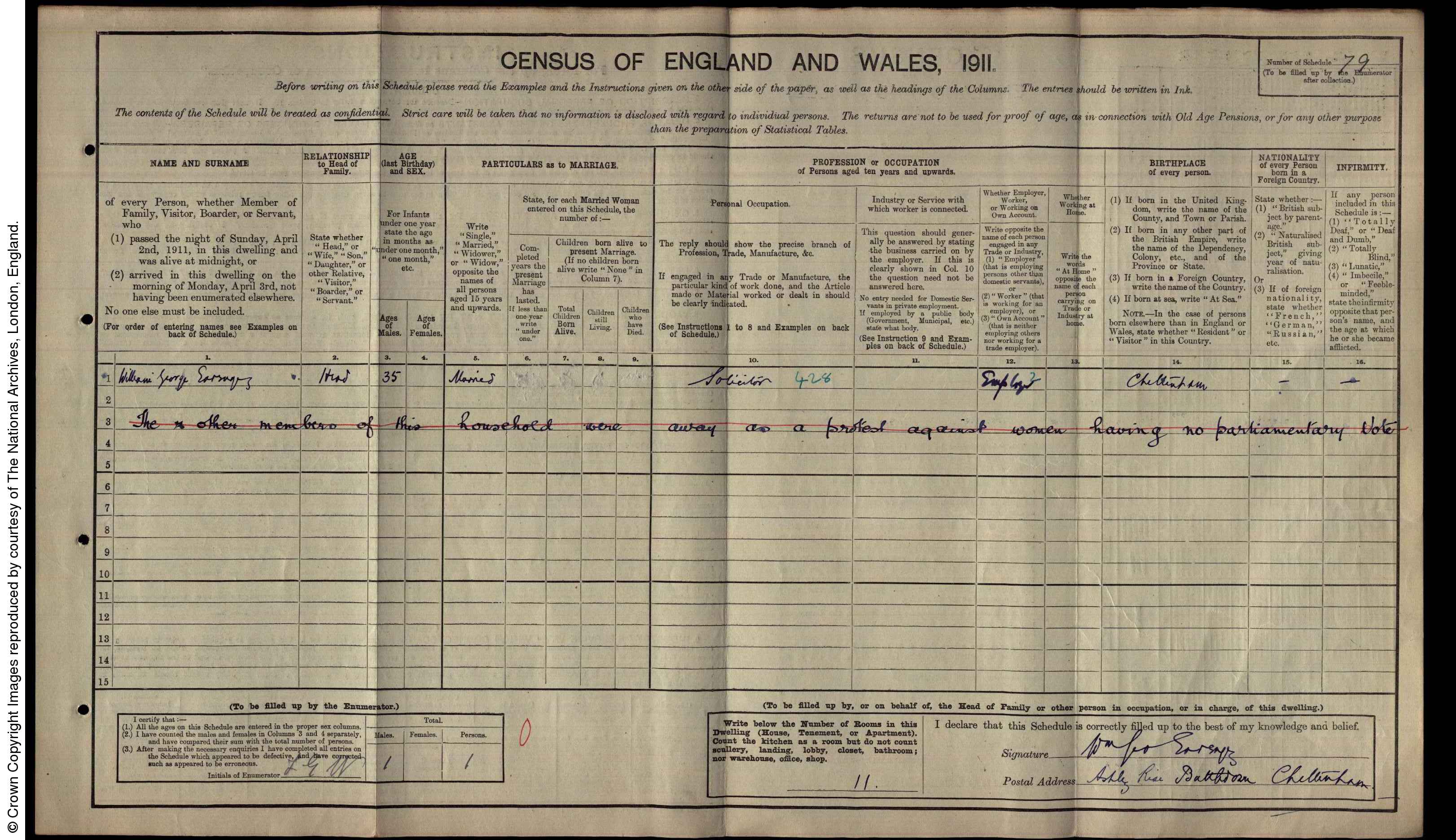

Census evasion in 1911

Although the Cheltenham WFL membership was small, it was a tightly-knit and active group. The most notable initiative, organised in the town by Florence with a parallel WSPU campaign, was the 1911 census evasion, an initiative aiming to distort government figures by persuading women to refuse to supply details for the census forms which, for the first time, were to be filled in by the householder rather than by a census enumerator visiting houses (see “No Vote, No Census” article). In correspondence in the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Echo, she opposed the Mayor, who felt that evasion would damage the chances of Cheltenham reaching the 50,000 population figure necessary to gain county borough status, and stressed the importance of local women ‘joining hands with our sisters all over the kingdom’.6 She herself evaded the census, together with her young daughter and whatever servants may have been resident.7

Census form for Earengey household 1911

Although William was himself a strong campaigner, as a local solicitor he could not be seen to risk committing an offence for which there was a potential fine of £5 or two months’ imprisonment, although he gave legal advice on the campaign to the national Executive and to his sister-in-law, Edith How-Martyn.8 Florence’s younger unmarried sister, Lilian How, who was living with her parents in Western Road and campaigned for the cause, also evaded the census.

Altogether 1911 was a lively year in Cheltenham. There was a by-election, at which the WSPU campaigned vigorously, and set up a more successful branch than the one Florence Earengey had tried to establish in 1906. In addition, an Anti-Suffrage League came to prominence. Florence maintained a measured presence throughout all this, and is reported as pressing questions on the speaker at a Town Hall meeting of this opposing group.9

She was always ready to participate in joint initiatives, and the WFL combined with the WSS and the newly formed Conservative and Unionist Women’s Franchise Association (CUWFA) to present the local MP, James Agg-Gardner, with an album of thanks for his stalwart but unsuccessful support of a Bill in the Commons to give a measure of women’s suffrage.10

Florence Earengey’s signature in the album of support given by suffragists

to James Agg-Gardner in 1912: for a list of Pittville signatories click here

Gloucestershire Archives D5130/6/6 (reproduced with permission)

She was also part of a deputation to discuss the various amendments to another Bill which had been put before the House of Commons for male suffrage only. She pleaded with Agg-Gardner to vote for anything which would allow the principle of women’s suffrage to be conceded, whether ‘one or a million women were enfranchised’.11

Cheltenham WFL banner

Women’s Library Collection (public domain)

Florence’s wartime activities can be followed in Neela Mann’s book, Cheltenham in the Great War (2016). After the war, the Earengeys left Cheltenham and both had distinguished careers as barristers. Florence became president of the National Council of Women of Great Britain and published a book on the legal and economic status of women.

1 Ironically, Elaine Oenone was able to be educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College as her father was a respected ‘professional’.

2 Cheltenham Examiner, 24 October 1906.

3 Cheltenham Examiner, 19 December 1906.

4 Cheltenham Examiner, 18 October 1912.

5 Cheltenham Examiner, 15/12/10. William continued to lead the WSS in various ways after the women’s split.

6 Liddington, J., Vanishing the Vote, p.160. Alderman Margrett and his wife were actually supporters of the women’s cause but on the less radical WSS wing.

7 There may have been no live-in servants as it appears that William has written ‘2 other members’ and crossed out the 2?

8 Liddington, p. 84.

9 Cheltenham Examiner 27 July 1911.

10 Cheltenham Examiner 12 April 1912.

11 Cheltenham Examiner 1 August 1912.