George Parker (1833-1907) – Pittville photographer

The proliferation of commercial photographic studios both reflected and recorded the social transformation of mid Victorian England. Cheltenham was one of the earliest towns in England to host a commercial photographic studio. The two earliest forms of photography, the daguerreotype and the calotype, were both announced in 1839 and were both subject to patent restrictions in England. The daguerreotype, a unique image on a metal plate, produced a sharp image and was preferred by early commercial photographers, while the calotype used a paper negative from which multiple positive prints could be produced, but its less defined image largely restricted its use to amateur photographers.

Britain’s first photographic studio was opened in London in March 1841. A Photographic Institution opened under licence to produce daguerreotypes in Cheltenham in September 1841 and operated more or less continuously with a succession of proprietors into the 1850s.1 In 1850, the studio was reopened by the American daguerreotypist Richard Low. But the introduction of wet-plate glass negatives with the potential for multiple prints of the same image at much lower cost led to a vast increase in both amateur and commercial photography in the 1850s. The demand for the daguerreotypes and ambrotypes produced by Low collapsed by the mid 1850s, which may account for his midnight flit in 1856. From this time on, Cheltenham was well served with photographic studios, up to a dozen working at the same time through the following decades. No doubt all of these were attended by the residents of Pittville at one time or another, but the studio of George Parker aimed especially to attract the custom of Pittville residents.

|

|

|

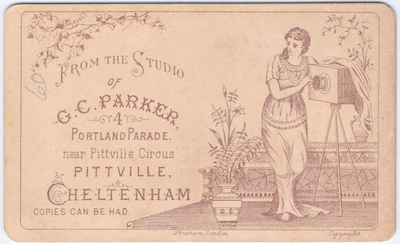

The elaborate back of the card mount of a carte de visite portrait photograph by George Parker in the late 1880s. The scale of commercial photography was such that a whole ancillary industry developed to produce decorative card mounts and fancy albums for displaying the photographs. This one was printed by Abraham in London. (courtesy John Simpson) |

George Parker joined the swelling throng of commercial photographers in England about 1864. It is a question where the operators of the photographic studios burgeoning across the country came from. All must have had some technical background. Many were artists.2 Others came from various technical trades. William Ruck was a medical galvanist before becoming a photographer on Montpellier Walk in the late 1850s. John Nott was a plumber before turning to photography in the 1860s.3 John Joyner, one of the most prominent of Cheltenham photographers, comprised both the trade and artistic backgrounds; he started out as a paperhanger and was recorded as a pupil teacher in the School of Art (and still a paper hanger) in the 1861 census. Parker, himself, was a cabinet-maker and may have got his start in photography by making his first camera body.

Parker was born about 1833 in the vicinity of Woodmancote or Bishop's Cleeve, adjacent villages to the north of Cheltenham. In 1851 his father was an agricultural labourer and the 18-year-old George was probably near the end of his apprenticeship as a cabinet maker. The family was then living in Cheltenham. By 1861 Parker was evidently a successful cabinet-maker, with a wife and two small daughters. But in the following years what may have begun as an amateur hobby – or as a sideline in making camera bodies for other photographers – became a career. With family responsibilities Parker must have been confident of the opportunities to be had as a photographer when he established a studio at 2 Winchcomb Place about 1864, close to the grand entrance to Pittville.

Only a small number of Parker’s photographs have been identified, but these span nearly the whole range of his career. Most of these are cartes de visite. This type of photograph was generally an albumen print taken from a wet collodion glass plate negative and mounted on a rectangular card approximately 2.5 x 4 inches (63 x 100 mm). This format was introduced into England from France in the late 1850s and its widespread adoption is indicated by the appearance of the term in advertisements in Britain in 1860.

|

|

|

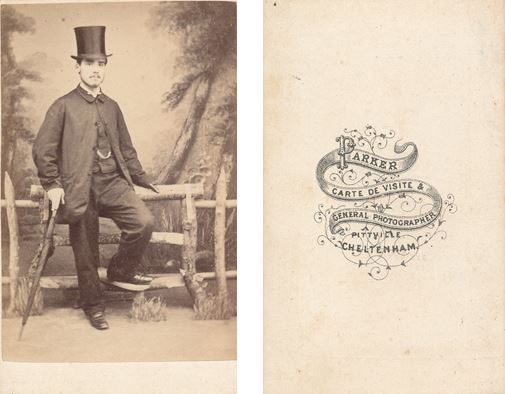

Young gent with top hat and umbrella in a rustic setting, late 1860s. This is in fact a studio portrait with a painted backdrop and mocked-up stile. The umbrella adds to the outdoor conceit. (Reproduced with permission) |

The backs of the card mounts of cartes de visite became increasingly elaborate as the nineteenth century wore on. Very early examples often had only the name and address of the photographer in plain letters. The earliest Parker carte de visite had a more florid and decorative back describing him as a ‘carte de visite & general photographer’. As cartes de visite portraits rapidly became the bread and butter of studio photographers in the 1860s, the explicit mention of it here suggests this is early in Parker’s career. Note also the absence of any border or lettering on the front of the card. It is curious that no street address is given.

|

|

|

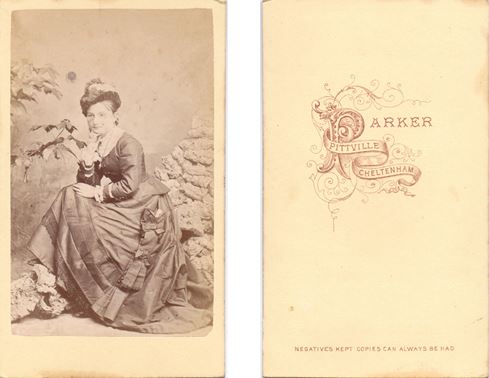

Studio portrait in another rustic setting, about 1870. The young woman is seated next to the branches of a tree on an indeterminate pile that may be intended to suggest a broken- down stone wall. The posture looks slightly uncomfortable, but shows off the decorative bows and tassels of the skirt to advantage. The pennant style of backmark is continued from the earlier mount but has become subordinated to a more dominant capital ‘P’ (courtesy Sue Rowbotham). |

Many commercial photographers numbered their negatives and noted the number on the back of the mounting card to facilitate further prints. The numbers were often four or five digits. In a busy metropolitan studio the number could reach six figures. Unfortunately, Parker did not number any of the known prints and only one of them is dated, so they are presented here in estimated chronological order based on the details of the card mount and the characteristics of costume and studio setting.

|

|

|

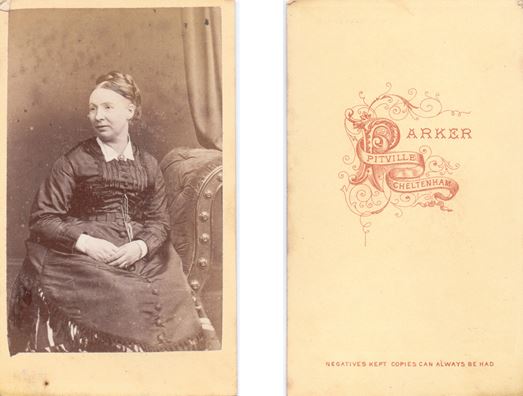

Woman in a plain studio setting, early 1870s. A curtain was often included as part of the backdrop to a studio portrait as will be seen in some of the subsequent Parker photographs. The mount appears at first to be the same as the preceding image but a slight difference in colour and the misspelling of ‘Pitville’ indicates that this is a fresh batch of card stock (courtesy Sue Rowbotham). |

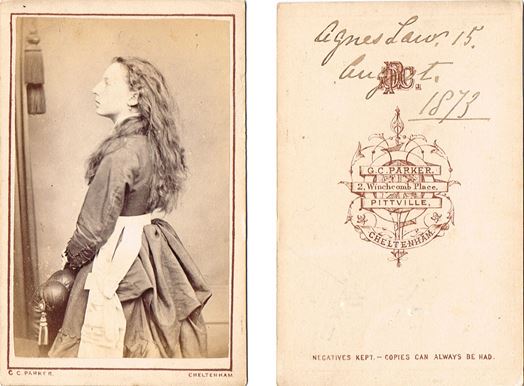

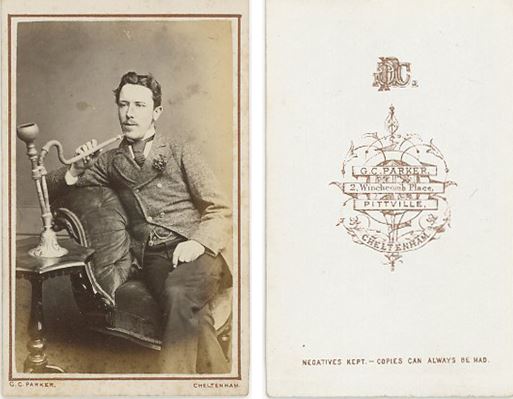

By 1873 Parker has a new card mounting, this time stating his address at 2 Winchcomb Place. Two photographs with this back are known. Now the back consists of three elements – a monogram of Parker’s initials, an elegant and symmetrical cartouche, and the note ‘Negatives kept – copies can always be had’. This all conveys the sense of an established and enduring business. The front of the card is also printed with a border for framing the albumen photograph and Parker’s name and the town name – Cheltenham. Altogether, the result was a smarter finish. The character of the photographs has changed also. The painted backdrop and rustic fittings have gone, with discrete furniture and the hint of a curtain.

|

|

|

The 15-year-old Agnes Law, daughter of the Earl of Ellenborough, photographed in August 1873, shortly before the marriage of her sister Eva. This is an all-too-rare example of a carte de visite with the name of the sitter and the date of the photograph (private collection). |

|

|

|

Young man with a hookah, mid 1870s. Sitters were often presented with an accoutrement indicative of their character or background. The hookah is suggestive of a connection with the near east or middle east. Many of the residents of Cheltenham had connections with diverse parts of the British Empire4 (courtesy Roger Vaughan). |

In 1881 Parker was still living at 2 Winchcomb Place. His household then consisted of his wife Elizabeth, his unmarried daughter Agnes (25), a dressmaker, and his widowed daughter Georgiana F. Smith (23), a milliner, and her infant son Frederick.5 There were no domestic servants.

|

|

|

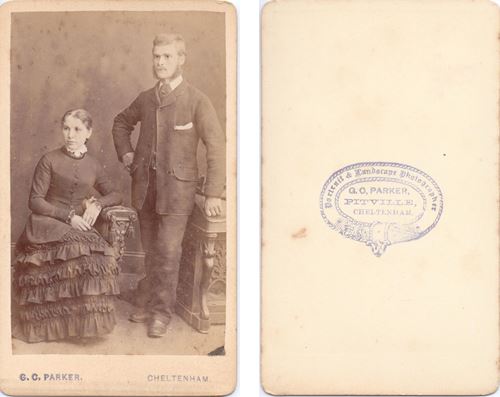

A young husband and wife, 1880s. The wife’s left hand has been posed to exhibit her wedding ring. The backstamp on this CDV is literally a rubber stamp. This stamp was used on CDVs of different dates and so is not a strong guide to dating. The rounded edges indicate a later date than the CDVs above (courtesy Sue Rowbotham). |

The backstamp is notable for claiming “Portrait & Landscape Photographer”. Did “Landscape” indicate a branching out of the business, and was this necessitated by a falling off of portrait business or an expanding of landscape business?

In the early 1880s Parker moved to 4 Portland Parade. This had been the address of the photographer Jonathan Peter Beach (1835-71), so perhaps Parker adapted an existing studio. In 1891 the household consisted only of George and Elizabeth and their grandson, Frederick William, now aged 12.6

|

|

|

This woman stands in the semblance of a domestic setting with the suggestion of a view through doors to a garden, late 1880s. Another photograph is known which shows a small child with a doll and apparently shows the same fur and curtain against a plain background. The back of this CDV is shown at the head of the article (courtesy John Simpson). |

|

|

|

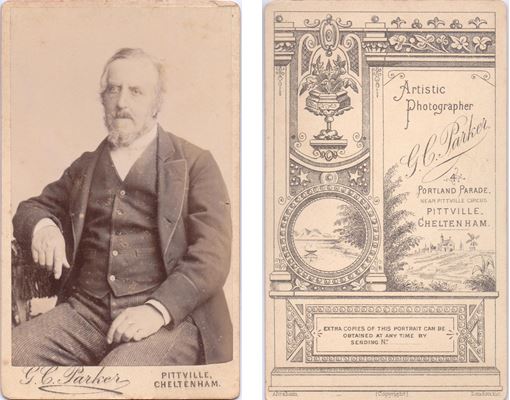

An older man, perhaps in his 50s, 1890s. In this and the next photograph, Parker shows the sitters in a three-quarter length close-up, with the setting diminished. This elaborate back, with its views and decorative elements, was printed in London by Abraham (courtesy Sue Rowbotham). |

All but one of the Parker photographs so far identified are in the carte de visite format. Following the success of that format a larger version, known as the cabinet card, was introduced in the late 1860s and became very popular towards the end of the century.

|

|

|

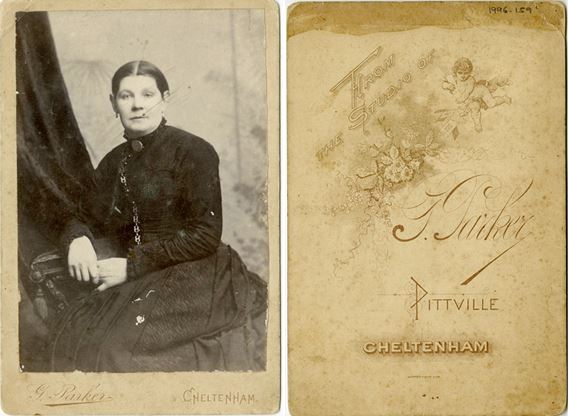

Cabinet card photograph of woman, early 1900s (courtesy Wilson Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum, 1996.159). |

As the printed backs of the card mounts became more elaborate, metropolitan firms specialised in printing them. Two of the Parker cartes de visite illustrated here are on cards printed by Abraham in London. It seems that systematic research on the printers of photographic cards has yet to be undertaken and Abraham remains unidentified. Perhaps the best known of card printers was Marion and Co of Paris and London. These firms probably had travelling salesmen with pattern books to take orders from local photographers. The last of the series of Parker photographs, the cabinet card shown above, has a printed back stylistically very different from the earlier mounts. It was printed by the Vienna firm of Bernhard Wachtl, which supplied printed mounts and other photographic requisites to customers across Europe and the eastern Mediterranean, even as far afield as Calcutta.

The 1901 census records Parker and his wife living alone at Portland Parade. He was working as a photographer on his ‘own account’ at home.7 He was still working as a photographer as late as 1906, still at 4 Portland Parade. He died in Cheltenham on 28 February 1907 at the age of 74.8 He had avoided the financial difficulties which led other photographers to bankruptcy, but the business was too competitive for him to have secured a comfortable retirement.9

It is curious that Parker never seems to have advertised in the local newspapers. The only clue to his promotional methods is an advertisement in the Positions Vacant columns of the Cheltenham Chronicle in 1888 for ‘respectable, energetic Men’ wanted as canvassers. He offered ‘Liberal terms to suitable applicants’ and as the advertisement appeared in April it seems likely that Parker was gearing up for an influx of new residents in Cheltenham for the spring and summer. Perhaps this was his regular practice.10

The longevity of Parker’s photographic practice testifies to his accomplishment as a photographic artist, a technician and a businessman. The photographs are well executed but largely conventional. The portrait of Agnes Law is the most dramatic and unusual. In his long career Parker observed the expansion of photography from the early days of its commercial success to the wide reach of snapshot photography brought by the introduction of the box brownie and the roll-film at the end of the nineteenth century.

Coda – Pittville in landscape photographs

Parker’s studio was well located to attract Pittville custom, but photographers were not confined to their studios. They went outdoors to record prominent historic sites, landmarks and buildings. Stereoscopic photographs of outdoor scenes were very popular from the late 1850s. ‘Topographic’ cartes de visite were also produced. These could be added to albums as souvenirs to complement the portraits of family and friends. These topographic photographs – individual albumen prints just like the portraits – were the forerunners of the printed postcards that became wildly popular at the beginning of the new century. They were often published by local stationers.

While one of the photographic backs indicated that Parker was both a portrait and landscape photographer, none of Parker’s landscapes are known. But with parklands designed to appeal to residents and visitors, it is not surprising that Pittville attracted topographic photographers from an early date.

In 1852 Roger Fenton (1819-69), one of the most significant early photographers, famous for his Crimean war photographs, made an excursion to Cheltenham and vicinity. Pittville fell under his camera’s gaze. Later in the year he contributed several photographs to a publication, the Photographic Album, issued in parts with four original photographic prints in each part. One of his photographs was titled ‘Pittville Spa, Cheltenham’. The Athenaeum’s reviewer (13 November 1852) was not enchanted: ‘On such a dull November day as this on which we write, the heavy bridge, dark waters and leafless trees of Mr. Fenton’s calotype assume an aspect which very likely belongs to them at the present season, – but it is Lethe, not the fountain of health, that we behold.’ This may have been the same photograph that Fenton exhibited under the title ‘Pittville, Cheltenham’ at the Society of Arts in London that year.

A local amateur, the Cheltenham solicitor Baynham Jones, Jr (1806-90), who had been involved in the transfer of the daguerreotype licence for Cheltenham in the 1840s, had become sufficiently accomplished to exhibit photographs of his own in London in the 1860s. At the annual Photographic Society exhibition in 1861 he showed ‘Pittville Lake, Cheltenham’ (#416) and in 1863 two images of ‘Pittville Pump-room, Cheltenham’ (#170*, #428). Jones’s fellow amateur, the Cheltenham dentist George S. Penney (George Stothert Penny, 1820-96) also exhibited a photograph of ‘Pitville Lake, Cheltenham’ in 1861 (#192).

By the 1860s topographic photographers were publishing original photographs on a large scale. Prominent among these were Francis Bedford (1816-94) and George Washington Wilson (1823-93). Bedford made several visits to Cheltenham and issued stereophotographs of Pittville Lake about 1860. Based in Aberdeen, Wilson developed a large scale business of topographic photographs of many parts of Britain, including Cheltenham. Numerous photographs of Pittville scenes can be viewed on the website of the University of Aberdeen’s G.W. Wilson & Co. Archive.

By the end of the nineteenth century, with simpler, lighter cameras and roll-film, it was within the means of the ‘snapshot’ photographer to record excursions to recreation sites like the Pittville parklands while others could buy postcards that began to proliferate.

Julian Holland

March 2015

Acknowledgements

I am pleased to acknowledge the following for advice and/or permission to reproduce Parker photographs: Wilson Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum (Annie McCulloch), Ian Gee (Cheltenham Photographic Club), Sue Rowbotham, John Simpson and Roger Vaughan.

Notes

1 John Palmer, 1841-4, Henry R.J. Marklove, 1844-9, Richard Beard, Jr, 1849-50, Richard Low, 1851-6.

2 Several of the early Cheltenham photographers can be identified as artists. George Edward Alder (1827-1915) was listed as an artist in the 1861 census. Undoubtedly he learned from his mother Mary Ann Alder, a teacher of drawing. Alder was an early practitioner of photography in Cheltenham in 1854-5 before an itinerant career which saw him again in Cheltenham in 1862-70. Peter Skeolan (c.1816-71), who established a photographic studio in Cheltenham in 1858, was a miniature painter and profilist who was taking photographs in Manchester as early as 1852. His son Peter Paul Skeolan (c1837-89) was also a photographer. Richard Dighton (1824-91) came from a family of artists. Jonathan Peter Beach (c1835-71) was described in the 1861 census as an artist portrait painter shortly before becoming a photographer.

3 There are some very striking group portrait cartes de visite by Nott in the Wilson Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum.

4 ‘Safely at home in Europe [after service in the Empire], the middle class is free to flaunt Indian servants, eat curry, decorate the home with Indian knick-knacks, and generally to act out in a properly circumscribed fashion the nightmare-fantasy of “going native”.’; Suzanne Daly, ‘Kashmir shawls in mid-Victorian novels’, in Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 30 (2002), pp. 237-55, at p. 249.

5 It seems that Georgiana was widowed within months of marrying Frederick George Smith.

6 Frederick's mother, Georgiana Florence Smith, died at 4 Portland Place on 19 February 1885, at the age of 26. The Parkers’ elder daughter Agnes Matilda married Major Smith Homer in 1883. He died after a road accident in 1897, leaving her with three small children. The following year she married John Hubert Lewis.

7 In 1901 Agnes, who was licensee of the Black Bear Inn in Tewkesbury, became bankrupt and by January 1902 was again living with her parents at 4 Portland Parade.

8 Gloucestershire Echo, 2 March 1907. Parker’s widow, Elizabeth (80), is recorded in the 1911 census as living with the family of her daughter Agnes Lewis in Stroud.

9 Thomas Matthew Bird of Brandon Terrace went bankrupt in 1869 and J. H. Preece, formerly of Cheltenham, in 1898 (Cheltenham Examiner, 15 December 1869 and 9 November 1898).

10 It may have been in reference to a former canvasser that the following advertisement appeared in the Gloucestershire Echo, 12 March 1888: ‘I, G. C. PARKER, Photographer, give notice that David O’Hagan is not and has not been in my employ for past fifteen months, and I shall not be responsible for any moneys paid to him during that time. – Dated, 12th March, 1888. The Studio, Pittville, Cheltenham’.