Edmund Selous: "Pittville’s first bird-watcher"

Edmund Selous was a pioneer of modern bird studies.1 He promoted the study of birds by observation (a word he disliked2) as opposed to what were – in the first decade of the twentieth century - the traditional, invasive methods favoured by contemporary ornithologists: the shooting and collection of specimens for description and classification. He lived in Cheltenham, at No 19 Clarence Square, formerly the home of explorer Charles Sturt. Several of Edmund Selous's early, most influential books were published while he lived in the house. We are fortunate that he also left notes of his bird-watching activities in "Pittville Gardens".

Family background and early life

Edmund Selous came from a talented London family. He lived for many years as a boy and as a young man at No 26 Gloucester Road, Regents Park, near the Zoological Gardens. His father, Frederick Selous, was a member of the London Stock Exchange and was one of England’s foremost chess-players of the 1830s and 40s.3 His uncle Henry Courtney Selous, a painter and illustrator, lived next-door at No 24 Gloucester Road, and his other uncle Angiolo Robson Selous, a playwright, lived at No 28. Edmund’s grandfather Gideon Selous (also Slous) (1777-1839) was a Flemish portrait and miniature painter.

Edmund Selous, painted by his daughter Mary Payne

(reproduced by kind permission of Andrew Selous);

his house at No 19, on the south side of Clarence Square

To Edmund’s contemporaries, the most famous Selous was his brother Frederick, ironically a celebrated big-game hunter whose hunting exploits were eagerly absorbed by the reading public of the day (see his Wikipedia entry). Edmund himself was born in St Pancras, Middlesex, in 1857. In 1877 he entered Pembroke College, Cambridge, but left after a year. He next tried his hand at the law, joining the Middle Temple in November 1878, and was called to the Bar three years later, in 1881. Though apparently successful, he was not satisfied with his professional life, and he soon retired to devote himself to the study of natural history and literature. In 1886 he married Fanny Margaret Maxwell, the daughter of the celebrated popular novelist Mary Elizabeth Braddon and, after the birth of their son Gerald the family moved, in 1888, to Wiesbaden in Germany. They returned to live in Mildenhall, Suffolk in the 1890s, where their twin daughters Ella and Mary were born.

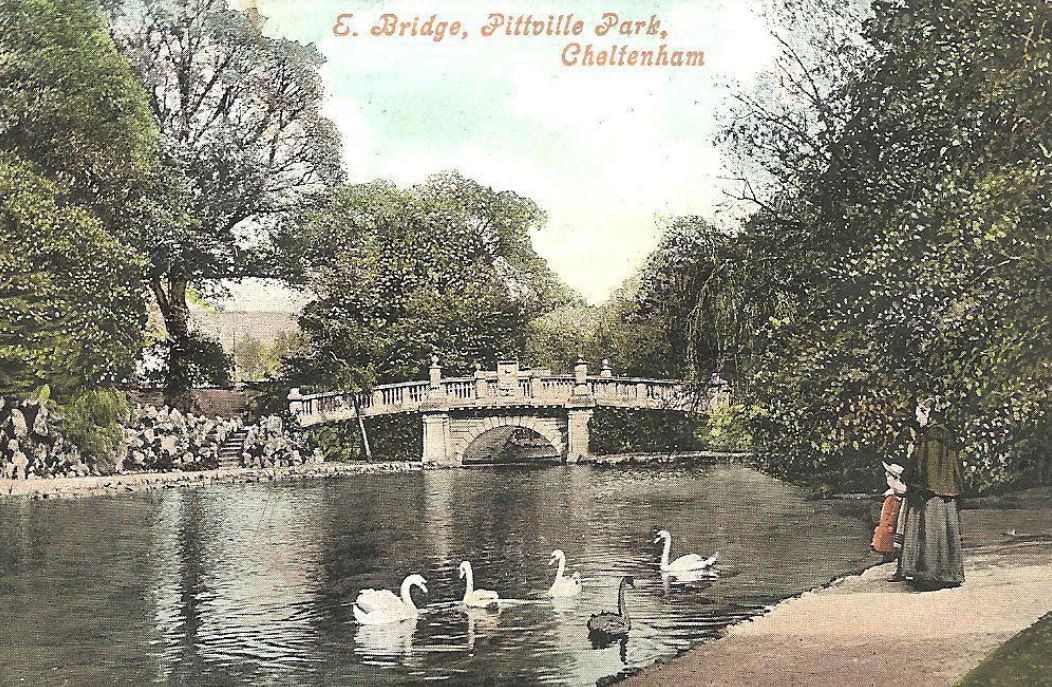

Swans on the lake at Pittville (1906)

Conversion to bird-watching

Edmund Selous’s original interest in ornithology was unexceptional and in keeping with the fashions of the times. But in his book Bird-Watching (1901) he explains his ornithological conversion:4

For myself, I must confess that I once belonged to this great, poor army of killers, though happily, a bad shot, a most fatigable collector, and a poor half-hearted bungler, generally. But now that I have watched birds closely, the killing of them seems to me as something monstrous and horrible; and, for every one that I have shot, or even only shot at and missed, I hate myself with an increasing hatred. I am convinced that this most excellent result might be arrived at by numbers and numbers of others, if they would only begin to do the same; for the pleasure that belongs to observation and inference is, really, far greater than that which attends any kind of skill or dexterity, even when death and pain add their zest to the latter. Let anyone who has an eye and a brain (but especially the latter), lay down the gun and take up the glasses for a week, a day, even for an hour, if he is lucky, and he will never wish to change back again. He will soon come to regard the killing of birds as not only brutal, but dreadfully silly, and his gun and cartridges, once so dear, will be to him, hereafter, as the toys of childhood are to the grown man.

He dates his conversion to studying bird behaviour to 1898, when he watched the antics of two nightjars, which he soon wrote up and published.5 His first book was actually for children: Tommy Smith's Animals, published by Methuen in 1899. He used to tell animal stories to his children, and "Tommy Smith" was his story-telling persona. He developed his revolutionary bird-watching theories through observation at his home in Icklingham, Suffolk, in 1899 and 1900. But the health and education of his children was put at risk by the family’s isolation, and in 1901 they moved (reluctantly) to Cheltenham, where his son Gerald attended the College.

Bird-watching in Pittville

Edmund disliked town life, but he found Pittville a suitable location for his bird observations. Notes that he made on bird activity in Pittville Gardens have been preserved in his archive at the Alexander Library in Oxford. They do not consist of lists of birds spotted, but of detailed accounts of typical bird activity, and his acute generalisations on the implications of his observations for bird study.

On 25 September, 1901, for example, he tells us that he was in Pittville Gardens early, between six-thirty and seven in the morning, and observed a mistle thrush continually chasing other birds (song thrushes, blackbirds, and robins) out of a yew-tree. As he watches, he notices that the mistle thrush’s behaviour changes: after the frenzied activity of driving out another bird it pauses and adopts a harsh, angry, scolding song with cadences less aggravated and more melodic, as if in triumph. The behaviour continues as more birds are chased out of the tree, followed by the "loud musical anger" which continued until the tree was empty of other birds. Edmund completed his remarks by pondering generally on the origin of bird-song, and whether it can be more marked in the breeding season.6

Mistle Thrush (Wikimedia Commons)

He regularly watched starlings, blackbirds, and other Pittville birds. He was not particularly interested in unusual species, but in the typical behaviours of common birds. Sometimes regular and irregular birds interacted, and this fascinated him. On 21 March 1902 he watched two black ("Australian") swans and two white swans on "the smaller of the two Pittville lakes". He will have been familiar enough with the mute swans, but the black swans evinced different behaviours.

This pair of black swans was nesting. Edmund had noticed them dragging sticks from the water to build a nest, and suggested to the park authorities that sticks be made available to the swans to help them in their nest-building. As his observations continued, he recorded that the black swans were more belligerent than the native variety. In addition, the black swans had a more successful aggressive strategy than the white ones: they acted in concert. When the white female swan was swimming close to the black swans’ nest, the black female closed in on her, forcing the white female to hesitate and turn back towards her black pursuer. At this, the black female became nervous, and emitted “that somewhat musical note” which Edmund rather anthropomorphically regarded as a call or part of a conversation between the pair. On hearing this, the male black swan joined the fray, bearing down on the white female while the black female fell into line behind him. The assault continued until the white female sought the sanctuary of dry land.7

These are typical examples of Edmund Selous’s field notes. There are not many from Cheltenham, but he made them wherever he observed birds: in Suffolk, in Shetland, and elsewhere. While he was in Cheltenham he copied up his notes and published them in a series of detailed and pioneering studies, including Bird Watching (1901), Bird Life Glimpses (1905), The Bird Watcher in the Shetlands (1905), as well as producing many other books of natural history.

In The Bird Watcher in the Shetlands he finds an opportunity to include his bitter criticism of the "Cheltenham Corporation" for interrupting his study of Muscovy ducks in Pittville. One day he went to the Gardens to continue his observations, and to feed the many Muscovy ducks that thronged to him, only to find that they had all disappeared. On enquiring of an attendant, he was told that the Corporation had "got rid of" his favourite ducks as a "mongrel lot", and had replaced them with a few less colourful species. He notes laconically that the Corporation had a precedent: it had got rid of the peacocks of Pittville Gardens.8

Edmund Selous’s legacy

Edmund Selous and his family moved away from Cheltenham in 1907, and travelled abroad to Germany and France, and elsewhere. He died on 25 March 1934 in Weymouth, where he had finally settled several years previously. Nowadays he is largely forgotten in Cheltenham. Even in his day he was little known, not being particularly sociable, and tending to write – especially in his later books – in a rambling, dense style in keeping with his view that every aspect of bird behaviour should be observed, recorded, and published. But today he is regarded as one of the pioneers of modern bird studies, a supporter of Darwinian ideas when they were unpopular, and a protagonist of modern ornithology well before Julian Huxley – who, unlike him, had the knack of popularising for the amateur and everyday reader. For modern bird-watchers such as Desmond Nethersole-Thompson "he was the prophet of a new generation".9 Without Edmund Selous we would not be able to trace the beginnings of modern ornithology to the very earliest years of the twentieth century.

John Simpson

I am grateful to the Alexander Library of Ornithology, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford for giving me access to the Selous Archive, and to Andrew Selous for permission to cite from the Selous Archive and to reproduce the portrait of Edmund Selous.