Retirement from the East Indies - in Pittville

These short biographies were written as part of the "entertainment" for a dinner held at the East India Café in Cheltenham by the Friends of Pittville on 17 June 2015. The story of each of the four Pittville residents was read aloud by a Friend, often with lively impersonations of their characters. But the stories themselves were carefully researched in advance and (despite some artistic licence from time to time) describe the lives of several Anglo-Indians who chose to return or retire to Pittville in the nineteenth century. In each case, the story looks for reasons why the individual may have chosen Pittville and Cheltenham, exploring the reasons why administrators, soldiers, merchants, and their families might have elected to take up residence in Pittville on their return from India, either in retirement or while passing on to the next phase of their lives.

The British East India Company obtained a royal charter to trade in the East Indies as early as 1600, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. Gradually, it saw off its rivals for this lucrative business, on the way even developing its own army, consisting of both British and Indian troops, to protect its trading (and later administrative) interests. The Company made treaties with local leaders, which gave it power to raise money through taxes. We often hear of Bengal, Madras, and Bombay (to use the old names) in the context of British India, and as time has passed their significance is sometimes forgotten. But it was in these places that the East India Company had its main headquarters and trading posts, placed strategically along the coast-line of the subcontinent: in Calcutta in Bengal, in Madras in the south-east, and in Bombay on the west coast. The Government in Britain was happy to manage the region at arm’s length through the Company, though it also sent its own forces to supplement the Company's army, and it expected the Company's Governor Generals and the administrative hierarchy to respond to British strategic demands.

The British East India Company obtained a royal charter to trade in the East Indies as early as 1600, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. Gradually, it saw off its rivals for this lucrative business, on the way even developing its own army, consisting of both British and Indian troops, to protect its trading (and later administrative) interests. The Company made treaties with local leaders, which gave it power to raise money through taxes. We often hear of Bengal, Madras, and Bombay (to use the old names) in the context of British India, and as time has passed their significance is sometimes forgotten. But it was in these places that the East India Company had its main headquarters and trading posts, placed strategically along the coast-line of the subcontinent: in Calcutta in Bengal, in Madras in the south-east, and in Bombay on the west coast. The Government in Britain was happy to manage the region at arm’s length through the Company, though it also sent its own forces to supplement the Company's army, and it expected the Company's Governor Generals and the administrative hierarchy to respond to British strategic demands.

All this changed in 1857-8 with the Indian Mutiny (or the Indian Rebellion as it is more correctly known today). The Mutiny started in the north-east of the subcontinent, in Bengal, where Indian forces rose up against the Company's rule, and it soon escalated into central and northern India. The Mutiny had numerous causes – resentment of the recruitment of higher–caste Indians into the Bengal Army (compared with a more liberal regime in Madras and Bombay), a perceived deterioration in the conditions of military service for Indians, as well as the breaking-point: the requirement that Indian soldiers use tallow- and lard-greased cartridges in their Enfield rifles. They had to bite the cartridges to release the powder, and biting the tallow-greased cartridges was offensive to Hindus (as tallow is made from beef), and biting the lard-greased cartridges was offensive to Muslims (as the lard was made from pork). The Company was clearly grossly insensitive, despite having been warned of the potential dangers of its practices. For many years opinion in Britain had been divided on how the Company ran India. Many felt that the Company was peopled by adventurers who were simply in India to line their own pockets, and certainly many fortunes were made there. After the Mutiny, the Government in London knew that it could no longer let the Company continue to manage India.

In 1858, after the Mutiny, the British Government assumed sovereignty of India from the Company. It established its own Civil Service, retaining Calcutta and the Bengal Presidency as its principal seat. According to one viewpoint, India was the "jewel in the crown" of Victoria's empire, but for others the British Raj (or "rule") was an exercise in oppression. After many decades of apparent stability, British rule came to an end in India with Partition in 1947.

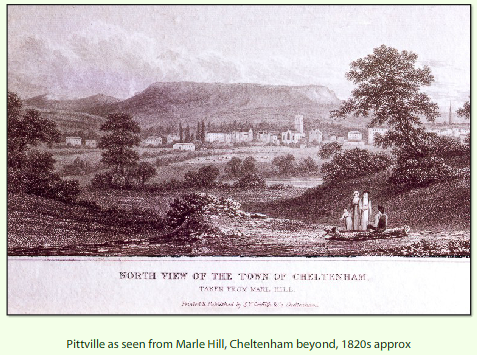

The people whose stories are told below are speaking as if in the year 1861, several years after the cataclysmic events of the Mutiny. Some returned to Britain as a direct result of this, while other families spanned the Mutiny - often with fathers working under the old regime, and their sons remaining in or returning to India under the new post-Company rule. The biographies offer the perspectives of both men and women, fathers and sons, long-stay Anglo-Indians and those for whom residence in India was only temporary. The first biography is that of Lewis Griffiths, a merchant in Madras who returned to Britain in the 1830s to purchase Marle Hill (now demolished, but then the big house looking down on the West Lake at Pittville).

[For a detailed examination of Anglo-Indian residents in Pittville, see Stuart Fraser's doctoral dissertation "Exiled from Glory": Anglo-Indian Settlement in Nineteenth-century Britain, with special reference to Cheltenham (University of Gloucestershire: 2003) here.]

Lewis Griffiths

"Ladies and Gentleman. You all know what a mansion is. If your Labour Party was now in power I would certainly be paying the Mansion tax, as I am Mr Lewis Griffiths, JP and Deputy Lieutenant of the County. I live in the grand house called Marle Hill, adjoining Mr Pitt’s estate of Pittville and stretching almost down into the town. I regret to say that some time after my death in 1869 the house was pulled down and some more modern structures erected.

You all know me – you glimpse me at the fashionable balls and society events of Cheltenham – as one of your established land-owners and plutocrats. It is now 1861, and I can look back over thirty years in Cheltenham with some pleasure. My boys attended the new Cheltenham College, before setting off on careers in the law, etc. My grounds have been improved under my enlightened governance. But many of you may be unfamiliar with the fact that all of this success started when I first visited India.

I was born in 1793 in the town of Bishop’s Castle in Shropshire – one of four brothers. As you may guess, we have all been rather successful. My elder brother John joined the India trade in the early years of the nineteenth century, and established a firm of merchants based in Madras. The firm of Griffiths, Wheeler, & Co dealt in costly goods from China and India, trading back in England, and also with the British establishment in India. I joined the family firm as soon as I could sail out there after leaving school. Soon Mr Cook joined us, and we became Griffiths, Cook and Co. Mr Charles Cook and I married sisters - the Ferryman sisters, daughters of a quiet Sussex vicar - out in Madras, at the British base of Fort St George. You won’t know the trading currency that was used down in Madras – the Star Pagoda. It’s worth about 8 shillings. They made Mr Cook and myself rich.

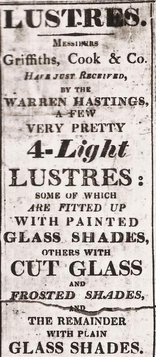

Here ar e some of the goods we traded in: tea, brought in on ships like the “Madras Merchant”, chinaware and – oh, all sorts of things on whatever ships were sailing – the Haman Shaw, the Soolimany, the Argyle, the Frederic and Maria – anything sailing out of and into Madras. We were always very proud of the “lustres” we acquired and sold – four-light candelabras that came in on the “Warren Hastings” in 1819, with their cut-glass and frosted shades.

e some of the goods we traded in: tea, brought in on ships like the “Madras Merchant”, chinaware and – oh, all sorts of things on whatever ships were sailing – the Haman Shaw, the Soolimany, the Argyle, the Frederic and Maria – anything sailing out of and into Madras. We were always very proud of the “lustres” we acquired and sold – four-light candelabras that came in on the “Warren Hastings” in 1819, with their cut-glass and frosted shades.

By the early 1830s we had so much money that we didn’t need to work any more. My wife and children accompanied me back to England on the “Duke of Roxburgh” in November 1830, along with various other returning families and officers.

We had looked around for somewhere to live in England. Why Cheltenham? We knew of the previous owner of Marle Hill, Lieutenant-Colonel Limond, from our years in Madras. And then my wife thought the new Regency architecture similar to some of the new buildings erected by the Company in India. I liked the climate, and being within reach of the rest of my family in Shropshire and Herefordshire. Then there was the school, for the boys – where they could go as day pupils. They liked country pursuits, and would met the right sort of chap there. Young Edward even rowed for the Oxford eight against Cambridge at Henley in 1847 (there wasn’t an official Boat Race that year). And the soldiers out in India were often talking about retiring to Cheltenham, Bath, Tunbridge Wells – places like that. Well, I had enough money, so why not?

That’s enough about me. You will want to get on with your appetisers. Allow me just to say that once at Marle Hill we continued to extend the family, to collect large amounts of money locked in probate cases from our days in India, and I hope contributed extensively to the smooth running of the upper echelons of society in our adopted county of Gloucestershire."

Mary Chapman

"Good evening to you all. My name is Mary Chapman, the wife of Robert Chapman, and we live at No 6 Pittville Terrace – that’s No 6 Clarence Road to you modern people. My husband is 34 years old, and he is a horse-dealer from Cheltenham.

When I tell you that he’s a horse-dealer, I don’t mean to imply that he trades half-wild horses at Cotswold village fairs. Nothing could be further from the truth. Like his father before him, he runs a livery stable in Cheltenham, and provides the carriages for the gentry of the town, as well as mounting gentlemen for the local hunts. He even mounted Bertie, the Prince of Wales, on one occasion. 1861 looks a very promising year for us, because this year the Grand National Hunt chase will be held in Cheltenham, and we are hoping that this may sow the seeds for a longer connection between the town of Cheltenham and the horse-racing fraternity.

It was through horse-dealing that I met my husband several years ago. But I was born in the East Indies, so we need to travel back there to find out why I am now in Cheltenham.

I was born Mary Hogg. My uncle James went out to India in 1814 after qualifying as a lawyer. He did extremely well out there, by dint of hard work and contacts. You will be surprised to hear that in 1839 he was made a Director of the East India Company (and even Chairman of Directors in 1846). As that implies, he was based in Calcutta, up in Bengal. Incidentally, he was the grandfather of Quintin Hogg, Lord Hailsham, whom you may remember.

His younger brother, my father - Charles Hogg - followed him out there, married, and then I was born – in Calcutta – in 1832. Father prospered, in his brother’s shadow and protection, and soon became the East India Company’s Solicitor, as well as being a director of various financial concerns. He even became Sheriff of Calcutta in 1848. There was a lot of money to be made out in Calcutta for the right people.

By 1851 my father was Secretary to the Bank of Bengal and was doing very well for himself. Sadly that year he fell ill and was forced to resign from his job and return to Britain. We all sailed back on the “Hindostan” to Southampton in June 1851. We wondered where to live. My father came from Belfast, and because of his financial and business background there was a rumour that he would stand as an MP for Lisburn in Antrim - but in the end he didn’t. I should have said that my uncle James was by now an MP for Beverley in Yorkshire.

In 1854 father made the decision to settle in Cheltenham. Why Cheltenham? Well, his health had been poor, and it was recommended that he retire to a healthy resort – and he rather liked the idea of Cheltenham’s saline spa. But he also had friends here from his days in Calcutta: did you know that they call Gloucestershire “The Calcutta of the Cotswolds”? The College was a deciding factor, as my brothers could be educated locally as gentlemen – in fact my father was soon asked to sit on the Board of Cheltenham College, where he joined several others with Anglo-Indian backgrounds.

And then there was the hunting. The Hoggs had always been hunters, out in India. Cheltenham was well-known as a sporting town, and my father rode with the Cheltenham Staghounds, with Robert Chapman. Everything fell together – a new life, a new husband, education for my brothers, and renewed health for my father – who survives to the age of seventy-four."

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Groube

"Good evening. Let me introduce myself to you. My name is Thomas Groube. I live at No 3 Pittville Parade (which you know as No 6 Evesham Road, on the left going out of the town). I’m sure you’ve heard of my father, Major George Bromley Boulderson Groube, of the 5th Madras Light Cavalry, Bellary. He is still out in India, preparing to return home. I live in Pittville with my mother, my seven brothers, and two servants - who came to Cheltenham with us when we moved up from the West County two or three years ago. It’s 1861 now. I don’t think I’ll be living in Cheltenham for long – it’s just a staging-post in my life.

My family have had close connections with India for at least two generations. My father, Major George Groube (son of Nelson’s Rear-Admiral Thomas Groube) was born in the military station of Fort St George in Madras back in 1810, and made his career in India. He married my mother in Bombay, after he had been out there about fifteen years. They say my father had a cushy number down in Madras on the Coromandel Coast. Here’s what somebody wrote about life in Madras at the time:

The Madras Presidency was to some extent the backwater of military life in India. Unlike the Bengal regiments, service by an officer in a Madras Regiment was unlikely to involve active field service. Generally, even for a junior officer, life was easy and rather routine, perhaps even mundane, with a large part of an officer’s time being taken up with sports and hunting.

I was born – like most of my brothers – in eastern India, at Solapure, when my father was on a posting there. We were all out in India until just three or four years ago – until the Mutiny, when everything changed.For the last three years I’ve been attending Cheltenham College. Actually, I’ve just left the college, and am preparing to start my military career. I did pretty well at school, but probably I’ll remember playing for the school rugby team best.

Why did we move to Cheltenham? Well, there are several reasons. Firstly, two of my cousins went to Cheltenham College about ten years ago. The school only opened in the early 1840s, but it had strong links with British India. They say that more old boys from the College were killed by tigers than from any other school in England! Also, I had many friends there whose family knew British India.

Our time in India came to an end as a result of the Indian Mutiny up in Bengal in 1857. Not many Madras forces were sent up to help, but my father’s 5th Madras Light Cavalry did go. That was where he received his only campaign medal, the Indian Mutiny medal. But after the mutiny, his regiment – along with the other East India Company troops – was disbanded. He’s not home yet, but we’re getting the house ready for him in Cheltenham."

Thomas’s father didn’t return home until early 1862, by which time the family was planning to move away from Cheltenham to Bedford. As for Thomas, it was true that (as for many young soldiers) Cheltenham was just a staging-post in his life, and he was desperate to get back to the country he loved - India. A year later, in 1862, he was an ensign in the British Army, the 7th Royal Fusiliers, fighting in 1863 in North-west India. He was present at the defence of the Sunghas at the Umbeyla Pass, for which he was awarded a general service medal and clasp; after that he served in the Afghan War in 1879-80, and took part in the defence of Kandahar (for which he received another medal). He retired, a Lieutenant Colonel, in 1882, returning with his family to Devon, where he died in 1906.

Juliana Charlotte McDonell

"Let me introduce myself to you. My name is Juliana Charlotte McDonell, and for many years now I and my family have lived in Pittville House on Wellington Road. That’s the big house looking down the middle section of the Pittville grounds, with its beautiful trees and private walks. As you doubtless know, my son William gained a Victoria Cross for his bravery during the Indian Mutiny – but more of that later.

I was born out in India in 1802. My father, the Reverend Nicholas Wade, was for many years the Chaplain of St Thomas’s Church, in Bombay. He married my mother out in Bombay in 1797. You may have read his Funeral Sermon for Marquis Cornwallis, then Governor-General of India, in 1805.

Now the question is – how did I come to be in Cheltenham? I have my mother to thank for that. My father, the Reverend Nicholas Wade of Bombay was taken from us suddenly in an apoplectic fit at the age of 56 one evening after a regular day at work, in January 1823. We stayed on in India for a year or so, so as not to interrupt my younger sister’s schooling, and then my mother started to look for a new home in England. She had been away so long that she was quite nervous about where to live. But we knew from all the references in the Bombay papers that there were towns like Tunbridge Wells, Leamington Spa, and Cheltenham that were favoured by old India hands. We had a few contacts in Cheltenham and Joseph Pitt was just starting to develop his elegant estate.

So in 1827 my mother Juliana Wade bought the site of Pittville House. It remained in our family’s use for the rest of the century. Sadly my mother died in Pittville in 1835, after only a short residence there. She was hoping to be joined by myself and my family, when my husband brought us all back from India. But it never happened.

I have just mentioned my husband. He rejoices in the marvellously aristocratic and Scottish name of Aeneas Ronald McDonell. He was one of many Scots in Pittville. After being brought up in Scotland, he travelled out to India in 1807 to join the old Madras Civil Service, in the days of the East India Company. We married in Bombay in 1819, when I was only seventeen. He was over ten years my senior. Our eldest son, also of course called Aeneas Ronald McDonell (as was his own eldest son) was born in 1824 – several other children followed as our family grew and grew, first in India and then in Pittville.

In 1839 my husband Aeneas decided to retire and return to Britain. Though he was the heir to a Scottish title, we had the option of living in the house in Pittville, and we took up that option. Before we left Madras he was given a wonderful party by his many friends, with colourful Indian dancing. It was all detailed in the Anglo-Indian newspapers at the time. I found Aeneas’s own farewell speech to his friends very moving.

Back in Cheltenham the boys grew up and attended Cheltenham College. In time young William and Thomas returned to India – William in the Bengal Civil Service and Thomas in the 6th Madras Light Cavalry, where he distinguished himself in the Mutiny on 1857. But it’s William I have to tell you about. William Frazer McDonell had joined the Bengal Civil Service in 1849, after years at Cheltenham College and then at the Company’s training school at Haileybury. At the time of the Mutiny he was Magistrate at Saran, in Bihar province, north-west of Bengal. It was most unusual for civilian to be awarded the VC. Here is an account of the action that led to his award, which was:

For great coolness and bravery on the 30th July, 1857, during the retreat of the British troops from Arrah, in having climbed, under an incessant fire, outside the boat in which he and several soldiers were, up to the rudder, and with considerable difficulty, cut through the lashing which secured it to the side of the boat. On the lashing being cut, the boat obeyed the helm, and thus 35 European soldiers escaped certain death.

William remained out in India for many years, becoming a Judge in Calcutta, before retiring in 1886 and returning to Cheltenham. You may have seen the blue plaque that the town placed on our house to celebrate his achievement."John Simpson