| Introduction | |

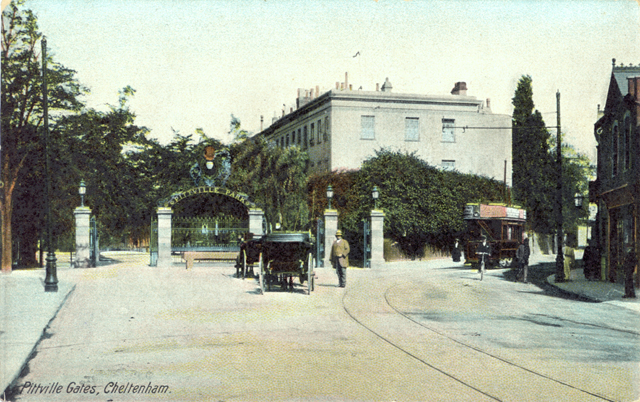

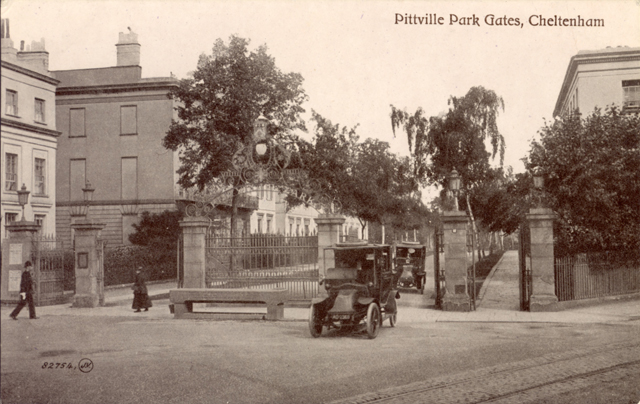

In the summer of 1833, the Scottish writer Catherine Sinclair visited Cheltenham. She wrote in her journal, later published under the title Hill and Valley (1838), ‘On Tuesday morning, we drove in a horse fly to visit Pittville in the suburbs of Cheltenham, a scene of gorgeous magnificence. Here a large estate has been divided into public gardens, and sprinkled with houses of every size, shape and character; ‑ Grecian temples, Italian villas, and citizen’s boxes, so fresh and clean, you would imagine they were all blown out at once like soap bubbles’.

Pittville is still a special part of Cheltenham, retaining much of the original development and attracting residents and visitors alike. Its origins lie in its medicinal waters, as did the phenomenal growth of the town as a whole during the nineteenth century. |  |

Cheltenham’s growth in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries | |

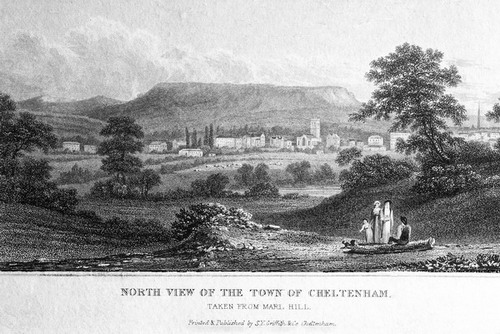

| Medicinal waters were first discovered in 1716, and Cheltenham gradually became a popular resort for the gentry, especially after the five-week visit of King George the Third in 1788. Five new spa wells, including that in Pittville, were in operation by 1834. Next to several of these were extensive tree-lined walks, rides and gardens in which people could walk, ride or drive by carriage. With a growing population and more visitors, demand for building land increased in the late eighteenth and early 19th century. The land alongside the walks and rides was seen to provide ideal sites for houses to accommodate the seasonal visitors and wealthy residents. It was also seen as an excellent business venture. |  |

| The timing of Joseph Pitt’s decision to establish a new spa and estate was influenced by both Cheltenham’s growth and by the national economic situation. Between 1801 and 1821, the recorded population of the town rose from 3,076 to 13,388 and the number of visitors to the spas also increased, both of which fuelled the demand for building land and houses. The pace of building quickened still further after 1820, as the country as a whole experienced an economic and building ‘boom’ with apparently unlimited capital available for investment in building. |  |

Joseph Pitt | |

| Joseph Pitt was born in Little Witcombe in 1759. He is said to have begun his career by ‘holding gentlemen’s horses for a penny; when, appearing a sharp lad, an attorney took a fancy to him and bred him to his own business’. He became an attorney himself around 1780 in Cirencester. He later invested the profits of his legal business in banking and in the purchase of land in Gloucestershire and Wiltshire, including substantial property at Cheltenham. His earliest recorded purchases here were of several small tracts of land to the north-east of the town from July 1789 onwards and over the next thirty years he became the single largest landowner in Cheltenham. He sold his solicitor’s practice in 1812 and was MP for Cricklade from that year until 1831. |  |

The creation of the Pittville Estate | |

| The future site of Pittville lay partly within Cheltenham parish and partly within Prestbury. The divided and piecemeal pattern of ownership of the area precluded its development as building land. To overcome this an Act of Parliament was obtained in 1801 whereby the Open Fields and other common lands on the north side of the town could be ‘inclosed’ into varying-sized allotments. These would then be ‘awarded’ to anyone who could prove ownership rights or other financial interests. A moving spirit behind the Act was undoubtedly Joseph Pitt, who was eventually to benefit from it more than any other individual. He also acquired land from other landowners. |  |

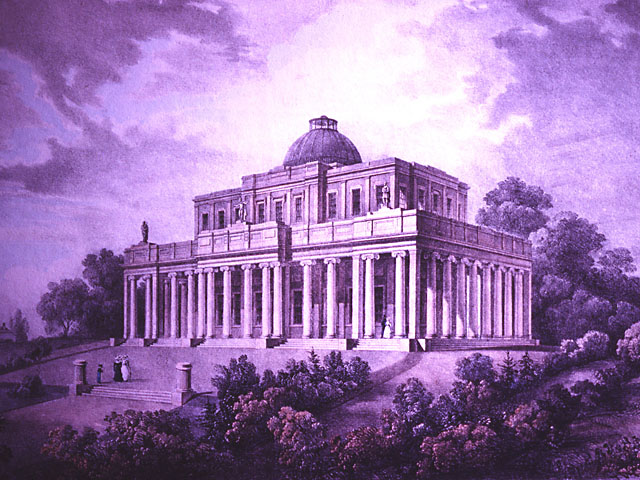

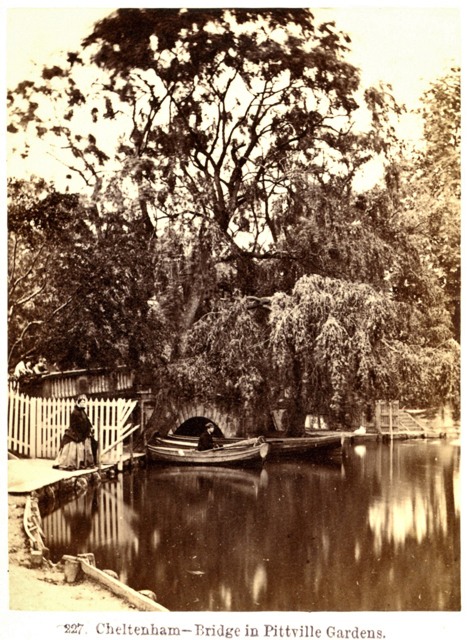

| Pitt’s scheme was for a new town, rather than an extension of Cheltenham. He envisaged an estate of approximately 100 acres, crossed by several miles of gravelled walks and rides, alongside which lots for between 500 and 600 houses were to be made available. These would accommodate both seasonal visitors to the new Pittville Spa and the wealthy people whom Pitt hoped would settle permanently at Pittville. The walks and rides would be planted with trees, and several ‘ornamental pleasure grounds’ would be created. This included a ‘Long Garden’ at the heart of the estate, between Evesham Road and Pittville Lawn, a residential crescent and two squares. There would be an ornamental lake, with a bridge across Wyman’s Brook at each end, beyond which, reached by a promenade lined with shrubberies, was to stand the Pump Room itself. Further north there would be a church. |  |

The designs for the Pump Room and for the general layout of the estate were entrusted to a local architect, John Forbes. Forbes had trained at the Royal Academy Schools in London and was working in Cheltenham by 1820. His proposed street layout is almost identical to that of today, although the density and arrangement of the houses is very different. His original plan, to provide a combination of villas and terraces, often alternating with one another, is best seen in parts of Evesham Road and Pittville Lawn.

The first medicinal well at Pittville was dug in 1822 and the foundations of the Pump Room were laid in May 1825. Other work started in 1824. |  |

A nurseryman, Richard Ware, was responsible for laying out the walks and rides and for planting the ornamental pleasure grounds. By 1827 the bridges at either end of the new lake had been built, several main sewers had been created, and a small subsidiary spa well, known as Essex Lodge or the ‘Little Spa’ had been established. The new Pittville Street, providing better access from the High Street, was ready by 1824.

The Pump Room was completed and opened to the public in July 1830. |  |

Forbes’s plans for the building lots were completed in July 1824. Each lot was to be offered freehold, subject to an annual rent charge, payable to Joseph Pitt. This was to contribute towards the general upkeep of the estate and the provision of a water-supply and sewers. The rent charges varied according to the size and situation of each lot. Each purchaser was to abide by certain restrictive covenants which, although varying slightly from lot to lot, tended to follow the same basic format.

The number and type of houses to be built were generally stipulated, as was the time-scale of their construction. Nothing was to be built forward of a ‘building line’ or the house had to be built in line with other adjoining houses. The purchaser had to agree to build to an elevation and external appearance approved and signed by Pitt himself and his architect and surveyor. |  |

The best example of this is the two terraces of five houses built in Pittville Lawn between 1836 and 1838 (numbers 45-53 and 59-67), in which the appearance of each house was to correspond exactly to the equivalent house in an earlier terrace of five houses further along Pittville Lawn (numbers 29-37). The internal layout of each house was solely the purchaser’s concern, and it is not unusual to find adjoining houses with very different room-plans.

Each house was to be built ‘fit for habitation with fit and proper materials and in a good and workmanlike manner’, the brickwork being faced with ‘well cleansed freestone or Roman cement’ and roofed with slates ‘not inferior in quality to the Countess blue slates’. The external appearance of the house was to be maintained and the number and placement of additional buildings such as coach houses, stables and greenhouses was often stipulated. |  |

| Once the house had been built, the land in front was to be laid out as an ‘ornamental pleasure ground’, and fenced with iron railings, in a style once again to be approved by Pitt, and often in unity with the adjoining houses. Seven-foot high brick walls were to be built on the other three sides of the property, the cost often being shared with the builders of adjoining houses. Purchasers were permitted to cut cross-drains into one of the estate’s network of sewers, and were responsible for laying down a pavement and gutter of ‘good tooled forest stone’ in front of their houses, either nine or ten feet wide according to situation. |  |

Commercial activities were restricted. For example, owners could not let a coach-house or stable separately from the house or sink any wells. The only professions allowed were librarians, nurserymen, florists, coffee house-keepers and hoteliers. Shops were limited to those in Prestbury Road. Two private schools were established, usually on condition that no signboard was erected outside the building.

Owners or occupiers had the right to use the walks and rides of the estate and the private gardens. Servants could only have access when in charge of the children of someone who was permitted to use them!

Other architects, in addition to Forbes, were appointed to design the houses. One was Henry Merrett, employed from 1836. The agreement between Merrett and Pitt suggests that, while the purchasers of terraced lots had to accept the elevations prepared by the estate architect, those who bought villa lots could select an architect and style of their choice, as long as the estate surveyor approved the designs. |  |

This may have been to encourage prosperous individuals to build and settle at Pittville and, in fact, no two villas in Pittville are the same.

Building lots at Pittville were first offered for sale in September 1824, and were eagerly taken up. However, circumstances beyond Pitt’s control were soon to interrupt the Estate’s progress, and many of the buyers failed to complete their purchases. It is not known how much Joseph Pitt lost but his financial collapse also meant that some of the proposed buildings such as the church were never constructed and fewer houses were built. |  |

| Building at Pittville, 1825 ‑ 1860 | |

Land at Pittville was bought by a large number of people, who built on it themselves, employed someone to build for them, or resold it, generally at a profit, to someone else. The last of these was particularly the case with those who bought a large block of land and then transferred it in smaller lots to individual builders.

The former was by far the smaller, only twenty houses having been built by their subsequent first occupant. Most of these were wealthy people who wished to have a house (usually a detached villa) in the style and location of their choice, and although some may have personally supervised the construction of their house, employing the necessary craftsmen, it is more likely that they engaged a professional builder. Several of these purchasers were women, while a significant number were military or East India Company officers. |  |

The second group of land purchasers at Pittville were the speculators, many of who were involved in the building industry and who no doubt personally undertook the construction of their houses. They included some of Cheltenham’s leading professional builders. Others were builders’ merchants, and specialist craftsmen, such as carpenters, painters, plumbers and bricklayers.

These craftsmen probably worked for the more substantial professional builders, but, especially during the building booms, were tempted to ‘go it alone’ and to buy some land and build houses themselves. |  |

Other speculators at Pittville were professional men already involved in some way with the practical, legal or financial aspects of building, such as architects, surveyors, bankers, and solicitors. There was also a small group of speculators who were in no way connected with the building industry, including a bell hanger, and a partnership between a draper and a widow. As with the wealthy intending residents who bought a building lot, these individuals may have employed a professional builder to construct their houses for them.

For the two hundred and eight houses where we know the identity of the original purchaser, seventy-four appear only once ‑ an indication of the very large number of people involved in building at Pittville. Indeed, only nine individuals are known to have been responsible for more than three houses. |  |

The prices paid for building land at Pittville varied according to a number of factors. These included the area and frontage of each lot, the number of lots purchased, their location within the estate and the level of demand for building land at the time of sale. Land was clearly more expensive during 1824‑25 than it was during the slump of 1826‑30, while the price of lots appears to have increased gradually from 1831 onwards.

Often, however, the prices paid for apparently similar lots varied so much that it is difficult to gain more than a general indication of price levels. |  |

| Many individuals who agreed to purchase a piece of land at Pittville signed a preliminary building agreement, incorporating the various covenants. This was followed at a later date by the formal conveyance of the land, once the title deeds had been prepared, at which time the purchase money was due. Once the agreement had been signed, building could begin. Evidence of exactly how builders worked is lacking, and although professional builders probably had their own workforce, the craftsman-builders presumably had to hire whatever labour was needed to complement their own skills, and perhaps even co‑operated with the builders of adjoining houses to pool their talents. |  |